86 years ago this Christmas, King George V sat down in front of a microphone to deliver what would be the first Christmas broadcast from a British monarch.

The Queens’ Speech, Christmas Broadcast or Christmas Message is something that’s watched by young and old, and, love or loathe it, it’s a festive tradition. It’s also an excellent example of PR with a very interesting story behind it.

The origin of the Christmas Broadcast

“I speak now from my home and from my heart to you all; to men and women so cut off by the snows, the desert, or the sea, that only voices out of the air can reach them.”

So began the first ever Christmas address in 1932. Over crackling radio waves, George V delivered his first festive speech after 22 years on the throne. The idea of a Christmas broadcast was first suggested by Sir John Reith, the founding father of the BBC some years previously. He put the idea forward as a way of inaugurating the new Empire Service, now called BBC World Service. George V reluctantly agreed and read a speech that was ghost-written by Rudyard Kipling.

Clearly, having the King give a speech on the new service was a powerful PR stunt for the BBC, establishing it as the true voice of Britain around the world, but the speech worked both ways. The broadcast gave George V a platform that enabled him to clearly define himself, the values he stood for and the principles by which he wanted his subjects to live. As a marketer would describe it, it was a chance for him to define his brand and to engender brand loyalty in a global audience.

The message was delivered to around 20 million people across the empire and it was a major event. People around the world gathered around their radios and the speech was even distributed by the Post Office so it would reach Australia, Canada, India, Kenya and South America where the radio broadcast wouldn’t reach.

Unsurprisingly, it went down rather well and in the following three years, he used the broadcast to inspire “hope and confidence” for the future, to admire the advance of technology and British ingenuity, to reinforce his position as head of the British Empire, to celebrate royal family news and to underline the familial relationship between all the nations within the empire. He also offered sympathy to people who were in distress, called for hope, peace and goodwill and encouraged people to aim for “prosperity without self-seeking”. His speeches were short and sweet (his first one was just 251 words long) but they set a template that’s been followed (almost) every year since.

The King’s Speech

If you’ve seen the 2010 film The King’s Speech, you’ll know the background of the Christmas messages that followed.

A year had passed in which George V had died, only to have his direct heir abdicate just months before Christmas. This broke the new tradition of the Christmas Message after just four years. Fortunately, George VI managed to make his way through his first broadcast in 1937, but (partly due to his speech impediment and discomfort in public speaking) he avoided making a second speech the following year.

In 1939 however, the country needed its leader more than ever. With voice-coaching, George had managed to show leadership on the airwaves by declaring that Britain was at war with Germany. It hadn’t been enough to fully repair the royal family’s tattered reputation, and the new king was still a relatively unknown entity and an easy target for mockery. It was through the Christmas broadcast that, like his father, George VI set out his stall.

“We feel in our hearts that we are fighting against wickedness, and this conviction will give us strength from day to day to persevere until victory is assured.”

George’s wartime speeches were confident, reassuring and calm. He spoke of his pride in the armed forces, gave thanks to their devotion and courage. These speeches redefined the monarchy, but one thing he included in them was even more effective.

More so than his father had, George VI frequently spoke about his family in his Christmas broadcasts and this helped to soften his image and make him much more relatable; the King, the Queen and the princesses were a family and in the speeches which mentioned them (all broadcast from their private home, Sandringham House) he let the people of Britain share in their Christmas cheer.

For families that were cut off from one another by war, this could have been a risky move, but George used the word ‘family’ as something which we could all share: We are all “one great family”. He was the nation’s King and his family was our family.

George VI reestablished the Christmas Broadcast as an annual tradition and he set a template which has hardly changed since.

“A priggish schoolgirl”

From the same desk and chair that her father and grandfather used to deliver their Christmas broadcasts, the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II continued the tradition. As her father had, she used her first speech as a chance to reflect on her father’s rule and to effectively introduce herself as monarch. Again, she referred to the commonwealth and empire as being like a family, emphasising that it “can be a great power for good – a force which I believe can be of immeasurable benefit to all humanity.”

While the Queen’s early speeches continued in the same pattern as her father’s, the world and technology were changing at a rapid pace. Although the BBC had been broadcasting since the end of the war and the Queen’s coronation had been the reason many people had bought TVs in the first place, the 1952 speech was the first one to be broadcast on television, albeit in sound only.

By 1956, ITV had launched and people were enjoying the first soaps and the first sitcom, Hancock’s Half Hour. Meanwhile, the first colour broadcasts were being tested. Across the country, television was becoming the norm and the Queen wasn’t on it. Five years after her coronation, the new Queen was in danger of appearing old fashioned, but that wasn’t the only threat to her reputation.

Crucially, the political situation was also changing: In November 1956, Britain experienced its most humiliating defeat as the Suez Crisis exposed the reality of Britain’s situation as a dwindling empire in a new world order.

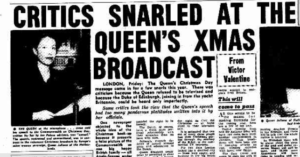

On Christmas Day 1956, the Queen gave her last untelevised speech and it went down pretty badly.

At the time, Prince Philip was on a voyage around the commonwealth and decided to give a brief radio broadcast of his own while aboard the royal yacht before the Queen gave her speech. The Queen shared her joy of hearing her husband’s voice and empathised with other families who were separated at Christmas. She did her usual routine of encouraging moral virtues; she encouraged her subjects to welcome refugees and advocated tolerance and acceptance across the commonwealth, but it was an awkward speech that didn’t sit well with the public.

Critics, no doubt upset after Suez, claimed it painted “a false picture of the Commonwealth as one big happy British family”. The royal family were in trouble: they were seen as being part of the same old-fashioned, weakened, meddling elite that made such a mess in Egypt and here was the Queen lecturing on morality and acting like everything’s fine.

Later in the year, life became more uncomfortable for the royals; the wife of Phillip’s private secretary began divorce proceedings, raising question marks surrounding the state of the Queen’s marriage and the consequences of Suez continued to churn.

Then, in August 1957, the peer and writer, John Grigg wrote a stinging criticism of the monarch which directly challenged her. Grigg, also known as Lord Altrincham took issue with the way the Queen presented herself and her style of public speaking, which he described as “a pain in the neck”:

“She appears to be unable to string even a few sentences together without a written text – a defect which is particularly regrettable when she can be seen by her audience… The personality conveyed by the utterances which are put into her mouth is that of a priggish schoolgirl, captain of the hockey team, a prefect, and a recent candidate for Confirmation…”

John Grigg, wasn’t an enemy of the monarchy; he wasn’t trying to bring the Queen down, he was pointing out what other people were thinking. In a way, Grigg was the PR expert that the Queen needed. With his experience in journalism and his grasp of politics, Grigg knew what they were doing wrong and he knew that they’d be in trouble if they didn’t turn things around. Even the Daily Express – which had attacked him at first – began to echo the same arguments: The royals needed to change.

Elaborating on his article for Pathé News, Grigg explained:

“I feel her own natural self is not allowed to come through: it’s a sort of synthetic creature that speaks – not the Queen as she really is.”

John Grigg put forward several recommended reforms which would help to make the monarchy more relevant for modern Britain and the Commonwealth and although he was condemned just as much as he was praised, many of his recommendations were eventually accepted.

He encouraged the Queen to surround herself with a more diverse group of advisers and courtiers, to replace her “presentation parties” for upper-class debutantes with more accessible “garden parties” that involved a broader range of people and, most noticeably, he encouraged her to move with the times and give her Christmas broadcast on television.

The Queen’s Speech

The Queen was given help to improve her diction, drafts of the speech were written by author, Daphne du Maurier and BBC announcer, Sylvia Peters gave her a tutorial on the “five best ways to make a speech on TV”. In the end, Prince Phillip helped her write the final draft and the Queen, nervous but determined, made TV history.

The Queen’s first televised speech was an enormous success and, together with the other changes that were made following Grigg’s article, it may well have saved the monarchy.

“I very much hope that this new medium will make my Christmas message more personal and direct.”

At 829 words, the speech is a whopper, but it was more direct and more informative than the speeches that preceded it and it had a pretty clear message: Modernity is great, but old traditions (like the monarchy) shouldn’t be thrown away like old technology.

In the speech, the Queen hit the same notes as her father and grandfather often struck; she emphasised the history behind her broadcast (it was the 25th anniversary of George V’s first broadcast), she celebrated the technology that “has made it possible for many of you to see me in your homes on Christmas Day” and she gave some virtue signalling, but she went far beyond it. She summarised how she and Philip had served her people throughout the year, she recognised the achievements of the commonwealth and shared it’s news and explained it to her subjects. She was also surrounded by pictures of her family, which all helped to paint the picture of her being a normal human being. Within eight minutes, she’d become, more accessible and more in touch than she’d ever seemed to be before.

Thankfully, her speeches are shorter now (imagine the groans around the dinner table if she was still reaching for a copy of Pilgrim’s Progress!) and they include more varied scenes, clips and even choirs, but the basic formula is the same and it’s still working for her.

She no longer gets dragged into using modern technology (last year’s speech was filmed in 3D and simulcast on social media) and, for many families, it just wouldn’t be Christmas without it.

So enjoy the Queen’s Christmas speech – or it’s officially named “Her Majesty’s Most Gracious Speech” – and have a very merry Christmas.